Change on the roof of the world: new book explores climate change and the Tibetan Plateau

Excerpt from the new book Meltdown: China’s Environmental Crisis by Sean Gallagher

Adapted By Caroline D’Angelo

With soaring mountains and vast grasslands, the Tibetan Plateau covers approximately one quarter of China. The plateau’s glaciers hold the largest store of freshwater on earth outside the North and South Poles. Though remote and sparsely populated, the plateau is of crucial importance to China and its downstream neighbors: Three of Asia’s most important rivers—the Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong—originate here.

Over the past 150 years, China’s average temperature has risen just 0.4 to 0.5 degrees centigrade. However, the high plateau has warmed much faster than the rest of China or anywhere else in the world – just like a roof on a hot summer day –

And the glaciers are melting fast. The Hailuogou glacier on the 23,000-foot high Mount Gongga retreated over two kilometers during the twentieth century alone.

Glacial-fed flooding has become a major problem throughout the watersheds. The grasslands, degraded by climate change and development, are losing their ability to soak up the spring melt. And so moisture rushes downstream and ironically, the soil left behind on the plateau gets drier. Warmer weather has increased evaporation rates, and without the sponge effect of healthy grasslands and peatlands, patches of the once lush grasslands are becoming barren brown desert.

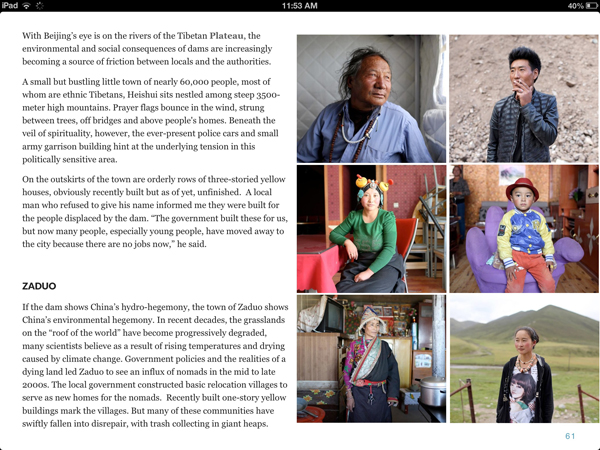

For 5,000 years nomads roamed the area with flocks of yaks, sheep and cattle. In recent decades however, the government, citing the grasslands’ degradation, has forcibly settled nomads and enacted laws to restrict grazing. Thousands now live in half-built “relocation villages,” where bittersweet memories of the grasslands give way to mounting piles of refuse.

“Life is more convenient now, but I worry that Tibetan culture is disappearing,” said one former nomad as people in a mixture of modern and traditional clothing walked by on the dusty streets of the town of Zaduo. While some like the business opportunities available in town, others struggle to make ends meet.

Another young man told me “There is nothing to do here except sell caterpillar fungus.” The fungus is used in traditional Chinese and Tibetan medicine, and the man worries that climate change will once again disrupt his livelihood. “The fact that the weather is getting warmer here each year isn’t good for harvesting caterpillar fungus. If we lose this, what will we do? How will we earn money?”

But other resources on the plateau are becoming more reachable with the warmer weather: minerals. Mining for gold, copper, lithium, lead, iron and coal has become a major industry – and it looks like the bounty could be huge.

This has increased tensions. A herder explains: “Tibetans believe that when the gold is mined, the grass is disturbed and it is very bad for the sacred mountains. The locals never try to get the gold from the mountains.”

There has also been an increased awareness about conservation. In late 2010, the Chinese government announced that it will “halt the loss of biodiversity in China by 2020.” It is a wildly ambitious target, but one that needs to be at least attempted before the traditions and landscapes of the plateau change forever.

An interactive map of the route author, Sean Gallagher, took through the Tibetan Plateau

— Post adapted by Caroline D’Angelo from “Meltdown: China’s Environment Crisis,” a new interactive e-book by award-winning photojournalist Sean Gallagher. Download a copy free from the iBookstore, Amazon, or Creatavist.