A jungle day-trip: studying brazil nuts in the Peruvian Amazon

By Eleanor Warren-Thomas

The day begins at around 5 a.m., when the sounds of motorbikes revving, dogs barking, wood being chopped and shouting men start to permeate the room. I haven’t needed to set my alarm for weeks.

I am here to help run a project on Brazil nut harvesting from lowland rainforests in Madre de Dios, in the Peruvian Amazon. Brazil nut collection from these forests forms a huge part of many people’s livelihood in this area, and the project aims to improve knowledge about the variation in Brazil nut production, which changes among trees and between years for as-yet unknown reasons.

Brazil nut trees, known locally as castaña, take decades to mature and start producing nuts in the wild, so the majority of the productive trees in these concessions are enormous – at least a meter across at the base – and are some of the tallest trees in the forest. Brazil nut trees are protected by law, and in some areas they stand alone in areas cleared for pasture. In many other areas, they form part of standing intact forest within concessions owned by local people, who walk well-managed trails through the forest each year to collect the nuts by hand.

Today we are starting out from the only hospedaje in the little town of Alegria, and will travel about 20 km along a dirt road to visit a castañero who lives in his Brazil nut concession. My colleague and I load the rear pannier of the motorbike with two rucksacks full of tents, food and multiple pairs of socks. Calling in at our favorite breakfast spot, we find that there is ‘no quinoa in town’ so make do with sweet bread and strawberry yogurt from one of the grocery shops. Sitting outside the shop, we attract the attention of two kittens who attempt to scale our trousers, and a puppy who finds he doesn’t have the ability to climb, but is happy to make do with finishing off the yogurt pot.

Squeezed onto the motorbike, we head along the tarmac road out of town, and turn off onto a red dirt road. After rain, these roads take on the texture of butter and are perilous for motorbikes, but today it is dry and fine. The morning is cool and the clouds are low, rubbing out the tops of trees and swirling across the road. We fly along the road and the plastic bag full of eggs and bread that I am clutching flaps madly in the wind. The road is full ofhazards – soft rivulets of mud, hidden bumps, the occasional wooden bridge – requiring expert driving.

Forty minutes later we arrive, windblown, under an enormous mango tree dripping with fruit that guards the front of our host’s house. Set in a field of tough tropical grass are several wooden buildings that house grandparents, a daughter, a son and their spouses. Ducks and chickens roam about amongst the fallen fruit, and two dogs bark in cautious greeting. It is mango season here, and the soft thumps of fruits hitting the ground are frequent. We are invited into the kitchen, an airy building with a handmade thatched roof, where a neat three-ringed charcoal burner made of compacted mud is roaring. Two cups of hot “chapo” are handed to us as a welcome second breakfast – sweet plantain mashed with sugar and spices using a specially selected stem of a young “quillabordon” tree that naturally forms a whisk-like shape.

As the day starts to heat up, our 77-year-old host dons his canvas shoes, picks up his machete and leads us into the forest. We quickly leave the strong sun behind on the open road and enter a perfect green corridor as we follow a narrow logging road into the forest. The huge tire tracks have formed long-lasting puddles in the soft clay soil, that are filled with tadpoles. This part of the forest feels special – we walk for about half an hour without encountering any logged trees, and the forest seems particularly dark green. Hidden birds shout from all around us, and the soft mud reveals the presence of deer, peccary and agouti. The soft ground after rain tells all sort of secrets – in other forests we have seen fresh tapir tracks only hours old, and even ocelot prints.

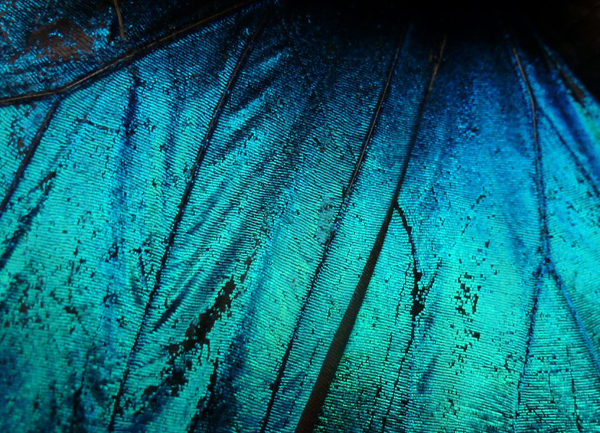

We veer off the road onto a carefully cleared path, the ground cloaked in big brown leaves from the towering castaña trees. As we crunch along, I have the odd impression of being on a walk through an English woodland on a summer’s day, until my eye is caught by a 6-inch electric blue butterfly floating along the path. Blue morpho butterflies seem to be found everywhere here, often in what seem to be leks of male butterflies flashing their wings at each other in clearings and on paths.

Brazil nut trees tower over us at regular intervals, some more than an arm-span in diameter and 40 meters high. The carefully maintained paths lead from tree to tree, each trunk cleaned of lianas and giving the appearance of columns holding up the green canopy. Piles of emptied “cocos” – the hard outer shells that contain sets of individual brazil nuts – lie at intervals along the paths, partially hidden under leaves and ready to twist the ankles of unwary walkers.

High-pitched squeaking from the trees betrays the presence of saddle-backed tamarins which peer inquisitively at us as we respond with our own squeaky noises. They seem reasonably confident around people despite the fact that they are often taken from the wild as pets here. In the past week howler monkeys, titi monkeys and spider monkeys have all also come within earshot, or even partially into view.

The presence of so many animals despite so much human activity in the forest is wonderful, and seems to demonstrate how fundamental the economic value of brazil nut trees is for the health of these forests. Although selective logging and hunting of local wildlife continues, the presence of producing castaña trees preserves patches of forest where its structure is undisturbed and the shade is deep and cool. Wildlife is persisting well into disturbed areas, but for me the dark green patches feel like safe havens.

After five hours of walking along forest trails our host leads us back to his house in time for lunch, where we are served rice, beans and fried plantain washed down with sweet tea. His wife and daughter spend the day in the house, preparing food for us strangers along with the family without a thought. At 77-years-old, our host understandably prefers to spend the afternoons napping on a bench in the shade of his mango tree, leaving us free to visit the stream that runs past the house and bathe in the sandy bottomed pool they have created through clever use of a log dam. Tiny fish swim about, palm trees provide shade overhead and the musical song of oropendulas drips from the trees. More tamarins swing past to peer at us, as we nibble on mangos and cool our feet in the water. I can’t help but smile as I think back on the day and hope to myself, long may the dark green persist.